Western world under oligarchs

Key Markets report for Tuesday, 3 February 2026

This is part 1 of a 2-part report; part 1 was published a few days ago on my personal Substack. Part 2 drops tomorrow. I believe this material is among the most important lessons for us to understand why so many aspects of our societies are dysfunctional.

World’s intractable problems

In his remarks to the United Nations General Assembly in October 2014, Noam Chomsky opened with the statement that, “Many of the world’s problems are so intractable that it’s hard to think of ways even to take steps toward mitigating them.” Since that speech, things only got worse and in addition to the festering social, political and economic crises plaguing the developed world, we find ourselves at risk of sliding toward another World War.

All this seems unnecessary and preventable; yet in spite of the fact that an overwhelming majority of people around the world abhor these developments, it seems oddly difficult for us to change course. Why are our economies chronically in crises? Why are the poverty rates rising? Why do we have people sleeping in the streets?

Modern industrial economies are extraordinarily productive, so how come we aren’t concerned about overabundance or anxious about how to properly enjoy all the blessings? Furthermore, given that all sane people around the world detest war, where does this state of permanent warfare come from? Is it from the democratic will of the people? Clearly not, since ordinary people almost always vote for anti-war candidates. Chomsky was right: we really are up against intractable problems.

Both parts 1 and 2 of this report are available in the YouTube video below (and no, it’s not AI):

The struggle between two systems of governance

To mitigate them, we need to explore where they originate from. To do that, we must start with the broadest possible context within which the otherwise perplexing day-to-day events are unfolding. In his speech to the World Economic Forum gathering in Davos in May 2021, George Soros offered an important clue.

He said that, “the world is increasingly engaged in a struggle between two systems of governance.” He contrasted the two systems as the open societies vs. closed societies. The same view has been affirmed by other Western officials including the former US Ambassador to NATO, Kurt Volker. He characterized the conflict as one between democracies and autocratic regimes or dictatorships.

However, in praising liberal democracies and demonizing dictatorships, people like Walker and Soros misrepresent the two systems, claiming that it is the autocratic regimes and dictatorships that are a threat to peace and liberty around the world. By contrast, experience shows that it is the crisis-prone Western democracies fomenting perpetual warfare around the world while increasingly embracing repressions and censorship at home. They have done so, not only over the last few decades, but since the birth of democracy, more than 2,500 years ago.

Democracies: in name only

In the Western world, we have been educated to celebrate and cherish democracy. Yet if we compare what our democracies deliver with what we’re told that they ought to deliver, we must acknowledge that they seem to deliver a lot of what the people dislike, like chronic crises and wars, while all too often failing to deliver what people do desire: peace, prosperity and security. That implies that at best, our democracies are ineffective at turning people’s aspirations into policies. At worst, they impede the democratic process by design.

In 2013, professor Thomas J. Hayes of Trinity University published a study analyzing the voting records of US Senators through five Congresses (107th through 111th) and compared them with public opinion surveys of over 90,000 respondents in the National Annenberg Election Survey. He found that in all of the five Congresses examined, the voting records of Senators were consistently aligned with the opinions of their wealthiest constituents. The opinions of lower income constituents appeared to never influence the Senators’ voting behavior.

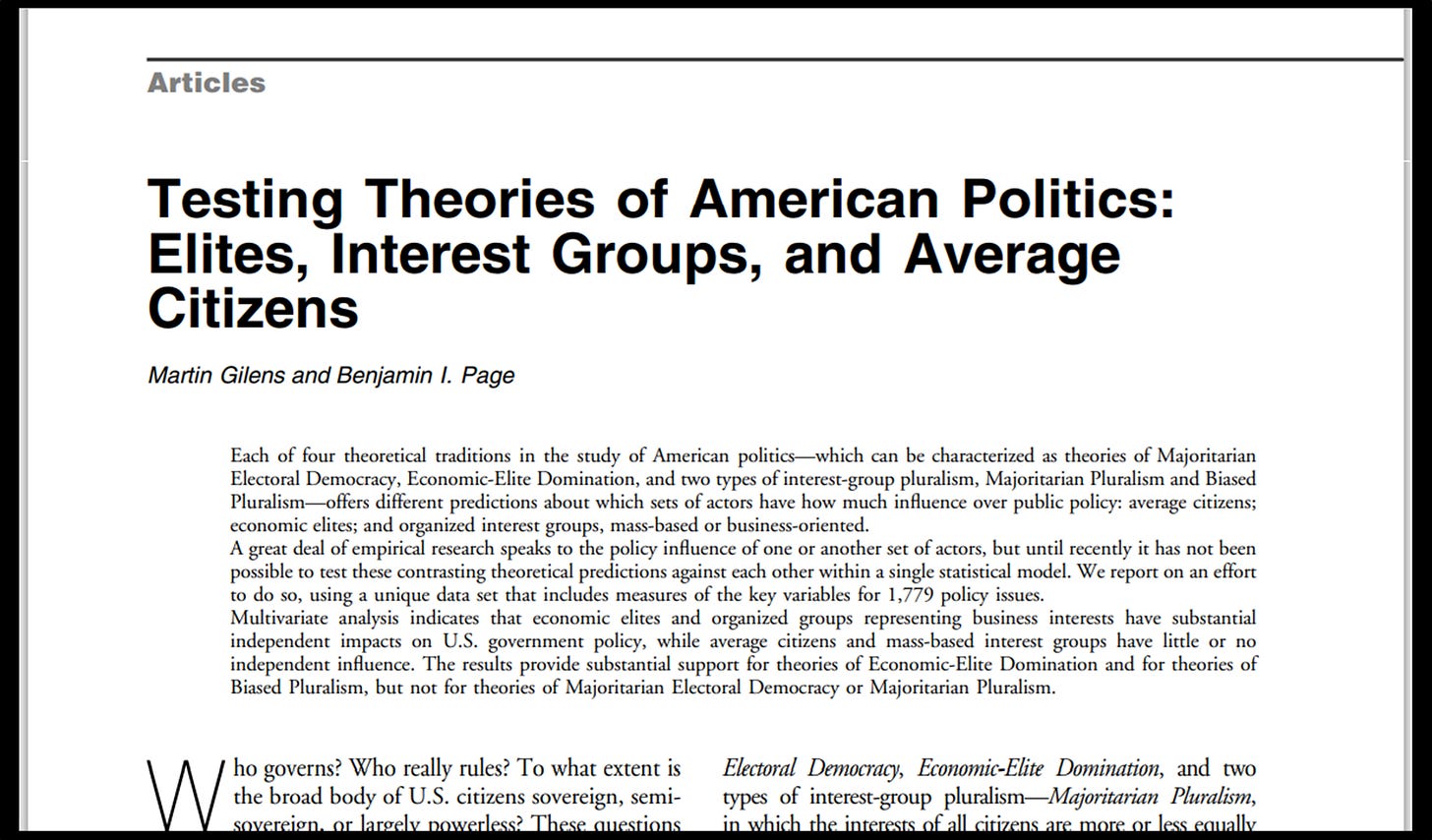

A subsequent study titled “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens“ by professors Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin I. Page of Northwestern University confirmed Hayes’ findings. Gilens and Page reviewed nearly 1,800 national surveys on public policy changes between 1981 and 2002. They concluded that, “Not only do ordinary citizens not have uniquely substantial power over policy decisions; they have little or no independent influence on policy at all.”

By contrast, economic elites are estimated to have a quite substantial, highly significant, independent impact on policy.” When, we might ask, do the ordinary people get the policies they favor? As Gilens and Page explained, even when 80% of the public favored some policy change, they only got that change when “those policies happen to also be preferred by the economic elites. ...” The implication of these studies is that the United States is in fact ruled by an oligarchy concealed behind the façade of democracy. The same is almost certainly true of most other western “democracies.”

This principle was discernible already since democracy’s birth. In Politics, Aristotle explained how, under democracy, creditors begin to lend money, demanding payment with interest. In this way, they acquire more and more wealth, turning democracy into an oligarchy. In making itself hereditary, the oligarchy then becomes an aristocracy.

And just as today’s “liberal democracies” abhor dictators and autocrats, democrats in ancient Greece abhorred tyrants. Rome equally abhorred kings, establishing the custom of assassinating or exiling any public official at a mere suggestion that they were seeking kingship. This is why Julius Caesar was assassinated in the Roman Senate. As we’ve come to witness in our time, the “No Kings” obsession is bizarrely still with us.

Rome under oligarchs: a brief history

Both as a Republic and as an Empire, Rome was one of history’s best examples of unrestrained oligarchic rule. According to historian Michael Grant and other sources, including Cicero, during most times since the overthrow of Rome’s last king in 509 BC, “twenty or thirty men from a dozen families” held what was almost “a monopoly of power,” with decisive control over financial and foreign affairs. Sallust, himself a lower-ranking senator, complained that a small faction of senators governed Rome,

“giving and taking away as they please; oppressing the innocent, and raising their partisans to honor while no wickedness, no dishonesty or disgrace is a bar to the attainment of office. Whatever appears desirable, they seize and render their own and transform their will and pleasure into their law, as arbitrarily as victors in a conquered city.”

Below this group of oligarchs was a wealthy “officer class,” which included the equites, or equestrians, a class of knights, so designated because their wealth qualified them to serve in the cavalry. Many of them were state contractors, bankers, moneylenders, merchants, tax collectors and landowners who occupied a social rank just below the aristocrats.

One magistrate estimated that the ranks of wealthy families in Rome numbered no more than 2,000. Below them was a mass of impoverished citizens, tenant farmers and slaves. The effect of the oligarchic rule was similar to what we could observe under all other oligarch-dominated democracies through history: they often engender an empire which replicates its own system of governance in colonies they control, sowing mayhem throughout the empire with perpetual warfare.

But while we know much about Rome’s imperial wars, we know much less about the conditions of daily life for the ordinary people in Rome. In “The Assassination of Julius Caesar,” Michael Parenti conveys some of the imagery from the epoch’s chroniclers.

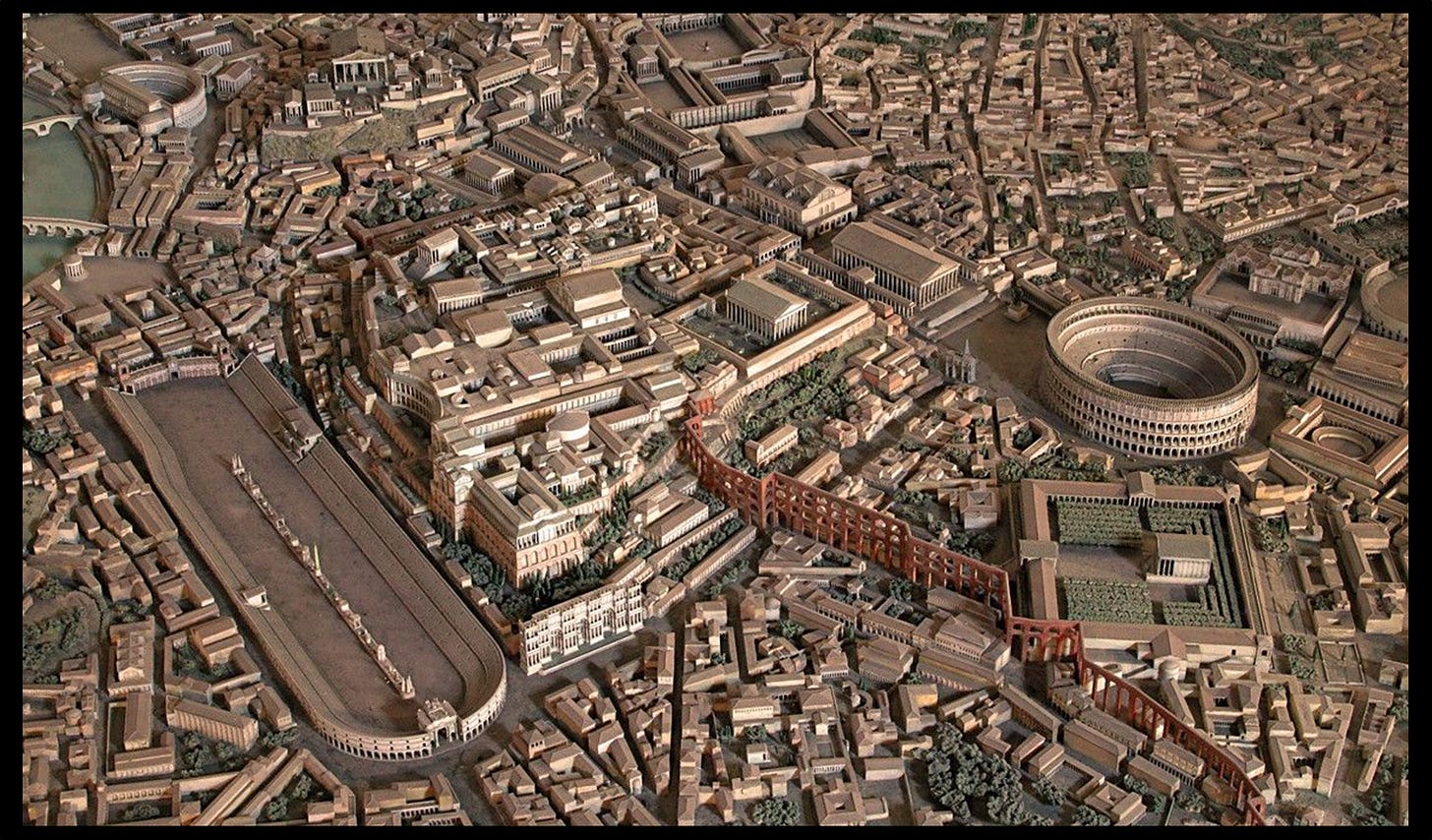

Splendor and slums

The eternal city’s downtown featured temples, emporia, public forums, ceremonial sites and government offices. But the center was surrounded by a dense ring of slums where tens of thousands of working poor lived in squalid conditions. In some places, the lodgings they occupied were piled up seven or eight floors high, all lacking toilets, running water, and decent ventilation.

Still, the rents for these crumbling quarters were usually more than the plebs could afford, forcing multiple families to reside in a single apartment. As Juvenal described it, “Rome is supported on pipe-stems, matchsticks; it’s cheaper thus for the landlord to shore up his ruins, patch up the old cracked walls... They are expected to sleep secure though the beams are about to crash above them.” Cicero himself was a slumlord. In a letter to a friend he wrote,

“Two of my shops have collapsed and the others are showing cracks, so that even the mice have moved elsewhere... Others call this a disaster, I don’t call it even a nuisance… There is a building scheme under way… which will turn this loss into a source of profit.” [1]

With rampant poverty came a high crime rate and insecurity. Rome had no street lighting and no police force to speak of. At night, the residents secured their families behind bolted doors. Only the most affluent, who could afford an entourage of servants to light the way and serve as bodyguards, dared to venture outside and only if necessary. Juvenal wrote that,

“It makes no difference whether you try to say something or retreat without a word, they beat you up all the same… You know what the poor man’s freedom amounts to? The freedom, after being punched and pounded to pieces, to beg and implore that he be allowed to go home with a few teeth left.”

Reformers and Senate’s death-squads

Rome’s frequent social crises led to limited legal reforms intended to redress the economic disparities and curb aristocracy’s excesses, but in practice such laws were routinely circumvented or ignored. Indeed, what we recognize as “lawfare” in modern parlance was one Roman oligarchs’ key levers of power.

Roman courts were staffed exclusively by the patricians and their agents with no checks on their arbitrary judgments. Writing around the turn of the New Era (BC/AD), Livy described the secrecy of Rome’s legal formulae, which were known only to elite patrician families. These “were decisive for any proper legal procedure, and were not published but remained under the well-guarded control of the pontifices for another 150 years.”[2]

In all, Rome’s oligarchic governance favored a steady and inexorable upward transfer of wealth, from the disenfranchised multitudes and colonial subjects to her parasitic oligarchy. As a consequence, Roman internal politics were marked by almost perpetual social and political unrest exacerbated by an overhang of unpayable debts, rolling civil wars, frequent colonial uprisings and periodic slave revolts.

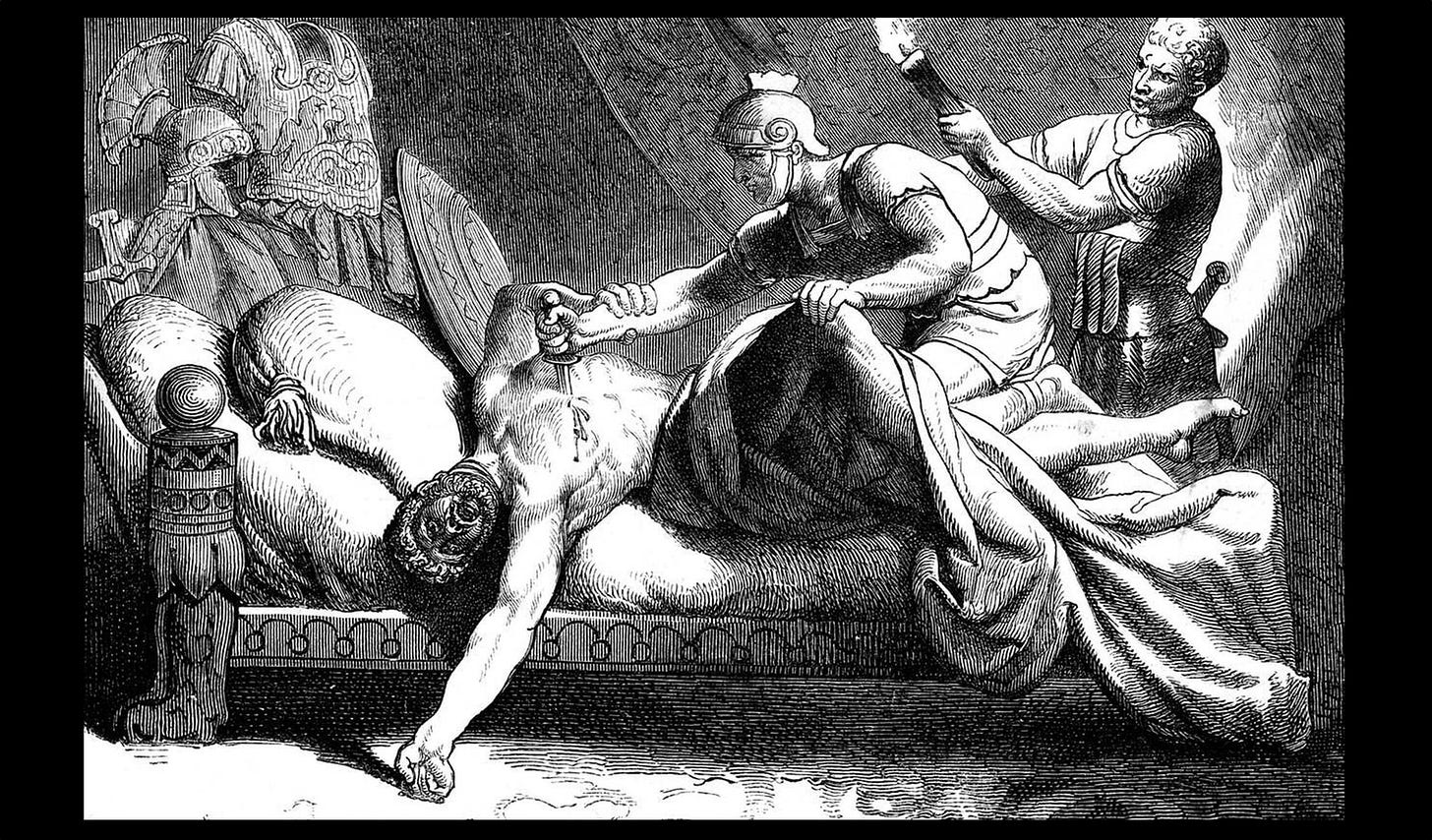

From the late 2nd century BC, a long succession of public officials, many of them of aristocratic birth themselves, understood that Rome was on the road to perdition and attempted to institute more far-reaching reforms. Among them were brothers Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, Lucius Appulleius Saturninus, Gaius Servilius Glaucia, Marcus Livius Drusus, Sulpicius Rufus, Lucius Sergius Catiline, Gaius Marius (Julius Caesar‘s uncle by marriage), Cnaeus Sicinius, Quintus Sertorius, Gaius Manilius and Julius Caesar.

With few exceptions they were all hunted down and killed by the Senatorial elite’s death squads along with thousands of their supporters.

Captives under an appearance of liberty

The assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC put the last nail in the coffin of social reforms in Rome. From that point on, the oligarchy ruled with few restraints, multiplying wars abroad and crushing all opposition at home through harsh repression and terror.

This system of governance ultimately devastated Rome’s economy at the same time as the costs of maintaining the Empire spiralled out of control. With her treasury depleted and too little left to take from the colonies and the working poor, the oligarchy turned their sights at Rome’s wealthy citizens.

In the first half of the 3rd century AD, Emperor Maximinus was short of funds he needed to pay his troops. Fearing that his troops might kill him if he failed to pay their wages, Maximinus started expropriating Rome’s distinguished families. Apparently however, what he was able to confiscate from them fell short and his troops did, in fact, kill him in 238 AD.

The chronic shortage of funds led to an overall decline of law and order and gangs of renegade pirates increasingly roamed the countryside, attacking towns and villages to pillage and plunder. Destitute freedmen and runaway slaves often joined these gangs as an alternative to serfdom. Herodian described the fear that gripped the elites themselves: “Although no fighting was going on and no enemy was under arms anywhere, Rome appeared to be a city under siege.”

Many Roman citizens sought salvation by emigrating to territories controlled by the barbarians. Writing around 440 AD, Salvian captured the plight of peasants struggling under the burden of unbearable taxation, abandoning their lands to break free from the terror of tax farmers and money lenders:

“they migrate either to the Goths or the Bacudae, or to other barbarians everywhere in power; yet they do not regret having migrated. They prefer to live as freemen under an outward form of captivity than as captives under an appearance of liberty….”[3]

However, not all could afford to emigrate. Those who couldn’t, surrendered their land and their liberty to patrician landowners in return for protection.

Massive enslavement of the population

As Salvian chronicled it, the process turned free men into slaves en masse. By the late 6th and 7th centuries, the devastation of the Western Roman Empire was almost total. Houses began to vanish from the archaeological footprint; dirt floors became the norm and the technique of building in mortared stone and brick was lost. Many basic crafts like wheel-pottery disappeared for a few centuries. The market for low-value functional goods and solid quality common usage items collapsed.

Without markets, coinage also disappeared and during its final stages, the Western Empire’s economy operated on barter. As a result of the breakdown of public administration and funding for public works, monumental structures begin to turn to ruin. Previously thriving cities emptied out, population levels cratered and Rome itself became desolate with shepherds tending their flocks among its crumbling relics.[4]

In part 2 of this report we’ll examine the experience of Russia under her oligarchs during the 1990s and Vladimir Putin’s elegant solution, which unsuffocated Russia’s society and economy and returned the nation to the rule of Law.

Notes:

[1] Michael Parenti, “The Assassination of Julius Caesar,” p. 28

[2] Michael Hudson, “The Collapse of Antiquity” p.211

[3] Hudson, 381-335

[4] On a much smaller scale and shorter time interval Sparta, another oligarch-dominated society, traced a similar trajectory to perdition like Rome.

To learn more about TrendCompass reports please check our main TrendCompass web page. We encourage you to also have a read through our TrendCompass User Manual page. For U.S. investors: an investable, fully managed portfolio based on I-System TrendFollowing is available from our partner advisory (more about it here).

Today’s trading signals

With yesterday’s closing prices we have the following changes for the Key Markets portfolio: